During the recent ‘refugee crisis’ Greece became one of the major entry points by sea as high numbers of refugees and asylum seekers, primarily originating from Syria, entered its territory en route to wealthier European countries. The unprecedented arrival of refugees has triggered mixed reactions towards newcomers raising socio-economic and cultural concerns about the potential impacts of refugees on the host country. The chapter uses survey data from the EU-funded TransSOL project and incorporates realistic group conflict and social identity theories to explore potential determinants shaping different attitudes towards Syrian refugees entering Greece. The descriptive analysis indicated that opposition attitudes towards Syrian refugees are widespread in Greece. Results from a multinomial logistic regression analysis demonstrated that individual determinants related to social identity theory are particularly important in understanding different levels of Greeks’ opposition towards Syrian refugees, whereas strong opposition towards the specific ethnic group was associated with an amalgamation of individual factors related to both realistic group conflict and social identity theory. The findings stress the necessity of implementing policy interventions that promote the intercultural dialogue and aim to mitigate the main sources of negative stances towards refugees.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Since 2015 the massive movement of forcibly displaced people, as a consequence of international conflict proliferation, including the war in Syria, has challenged Europe. European countries had to tackle one of the largest movements of displaced people through their borders since the World War II (UNHCR, 2018). The Syrian civil war has played a key role in the recent refugee influx into Europe (Lucassen, 2018). Since the start of the Syrian civil war in 2011 more than 5.6 million people were forced to flee to neighboring countries as well as several European ones (UNHCR, 2019). In 2016, first time asylum seekers applying for international protection in the European Union (EU) member-states reached the record number of 1.2 million, around 30% of them originating from Syria Footnote 1 (Eurostat, 2017). This unprecedented movement of refugees and asylum seekers Footnote 2 seeking safety in European countries has led to what has been called the ‘refugee crisis.’ Footnote 3 The term ‘refugee crisis’ is used to describe the movement, primarily under hazardous or extremely difficult conditions, of large groups of displaced people fleeing their home countries due to conflicts, persecution, wars or natural disasters and seeking safety in countries other than their own. The specific term can refer to the displacement taking place in refugees’ origin countries, in host countries or the potential hazards refugees face during their movement. Therefore, it involves the perspective of the refugees, of the counties to which they flee or both of them. For the rationale of the present chapter the term ‘refugee crisis’ refers to the perspective of the host countries facing significant challenges to effectively manage the massive movement of forcibly displaced people entering their borders.

The unprecedented arrival of refugees has caused different reactions among European populations. On the one hand, Refugees Welcome movements have emerged in different European countries to provide support and claim refugees’ rights (Nikunen, 2019; Chap. 8 in Papataxiarchis, this volume) but on the other, negative stances towards refugees have been reported primarily grounded on socioeconomic, cultural and security concerns (Dempster & Hargrave, 2017; Ipsos MORI, 2017). For instance, Wike et al. (2016) found that a relatively high percentage of European citizens perceived refugees as a threat to their cultural norms and economic resources; also that they were concerned refugees would increase the likelihood of terrorism and commit more crimes than other social groups. Moreover, the same study showed that more than half of participants supported the notion that Muslims were not willing to adopt the way of life and customs of the host countries, indicating that European citizens’ perceptions of Islam might impact on their attitudes towards refugees from the specific religion.

During the recent ‘refugee crisis,’ certain European countries had critical roles as transit (such as Greece, Italy or Spain) and as destination (such as Germany, Sweden or Austria) countries. In 2015 Greece became one of the major entry points by sea since a high number of refugees entered its territory en route to wealthier European countries. By the end of 2015, the total number of registered refugee arrivals in Greece reached the record figure of 821,000 with the bulk of the flow being directed towards the islands bordering Turkey (IOM, 2015). In 2016 the top nationality of refugee arrivals in Greece was Syrian refugees (European Stability Initiative, 2017).

Greece became one of the epicentres of the ‘refugee crisis’ activating mixed reactions towards newcomers and raising similar concerns as in other European populations about the potential negative impact refugees could have on the country. For instance, Dixon et al. (2019) argue that while more than half (56%) of the Greek population felt warm towards refugees and expressed substantial empathy for the newcomers, the majority of Greeks perceived refugees as potential threats to the country’s scarce economic resources. Furthermore, more than half of participants (51%) supported the notion that refugees would negatively affect the economy due to costs on the welfare system provisions. Similarly, in a cross-national survey conducted during 2016–2017 (Tent, 2017), the economic and cultural perceived impacts of refugees on the country were of greater concern among the Greeks compared to the populations in other host countries in the globe. Moreover, across ten European countries, Greece had the second highest prevalence of responses (69%) Footnote 4 supporting the view that a large number of refugees leaving countries such as Syria and Iraq constitute major threats to the country (Wike et al., 2016). Other studies support that the sizable refugee influx has fuelled the rise of neo-fascist parties in Greece (Dinas et al., 2019).

Given that during the recent ‘refugee crisis’ Greece has played an important role, primarily as a transit country, and has hosted a significant number of Syrian refugees, the main rationale of the present chapter is to explore Greeks’ attitudes towards the specific ethnic group entering the country. Using survey data from the EU-funded TransSOL project Footnote 5 and incorporating realistic group conflict and social identity theories I investigate potential determinants shaping natives’ differing attitudes towards Syrian refugees.

The present chapter contributes to related migrant research in two important ways. First, the analysis focuses on Greece, a country that has been challenged by the recent ‘refugee crisis’ while suffering one of the deepest recessions in its modern history. In times of simultaneous crises it is fascinating to examine how attitudes towards Syrian refugees have been shaped when the population has been strained by both the economic depression and the massive inflows of thousands of refugees. Second, the chapter attempts to unveil individual factors that trigger different attitudes including different levels of opposition towards Syrian refugees by providing empirical evidence on some key determinants in elaborating such stances. Understanding the individual determinants of anti-refugee sentiments is particularly important in designing effective policies that aim at modifying such negative stances.

The chapter is structured as follows: The following Sect. (5.2) discusses realistic group conflict and social identity theoretical frameworks and develops specific research hypotheses. Sections 5.3 and 5.4 present the methods applied and the statistical results, respectively providing some evidence on the main determinants shaping different attitudes towards Syrian refugees. Finally, the concluding Sect. (5.5) outlines the main findings and discusses how these might inform policy initiatives as well as recommends some future research directions.

The macro level factors primarily involve the state of the economy and the size of the migrant population in the host country. Adverse socioeconomic conditions (such as high unemployment rates) intensify the inter-group competition over scarce material resources whereas a sizeable migrant group implies a large number of competitors in the labour market which increase natives’ realistic threats and triggers opposition towards migrants (Lahav, 2004; Schneider, 2008; Semyonov et al., 2008; Sides & Citrin, 2007).

Although realistic group conflict theory emphasises the key role of material interests in shaping attitudes towards migrants, social identity theory underscores the importance of symbolic and cultural threat perceptions. These threat perceptions refer to natives’ fears that newcomers with distinct values, norms and beliefs threaten the cultural identity of the host country (Zárate et al., 2004). Proponents of social identity theory contend that individuals define themselves in terms of group membership and strive to achieve a positive social identity by assigning positive characteristics to the members of their own social group (in-group favouritism) at the expense of other social groups that they do not belong to (out-group discrimination) (Tajfel, 1981, 1982; Tajfel & Turner, 1979, 1986). Symbolic threats to the host country’s ethnic and cultural cohesiveness posed by migrants of different race, values, norms and religion are interpreted as threats to the native group’s identity; therefore, such threat perceptions may activate negative stances (Davidov et al., 2008; McLaren & Johnson, 2007; Sides & Citrin, 2007; Sniderman et al., 2004). At the individual level symbolic threats intensify among individuals, emphasising the unity and coherence of the native population as a group or as a ‘nation’ clearly differentiating itself from other ethnic groups (Pichler, 2010). Research has shown that natives’ preference for cultural unity across different European countries is one of the strongest predictors of hostility towards migrants (Ivarsflaten, 2005; Sides & Citrin, 2007). At the macro level symbolic threats can be triggered when a sizable migrant group is perceived as a threat to the ethnic and cultural cohesiveness of the host country activating negative stances towards migrants (Lahav, 2004).

Despite the importance of realistic group conflict theory and social identity theory in understanding natives’ attitudes towards migrants, some scholars advocate that such attitudes are formed in relation with the perceived identities and attributes (for instance, religion, culture, economic status, country of origin, etc.) of migrants per se which might activate different types of threat perceptions and in turn stimulate negative stances (Hellwig & Sinno, 2017). For instance, Ford (2011) found that among the British population opposition towards non-white and culturally more distinct migrant groups was higher than towards white and culturally more proximate groups, i.e. migrants from countries with stronger cultural and political links to Britain.

Based on the aforementioned research one could assume that refugees who originate from culturally distinctive countries will pose greater threats to the cultural unity, therefore, in accordance with social identity theory, they might attract more opposing attitudes. Because of Syrian refugees’ different cultural and religious background (most of them are Arab and Muslims) Footnote 7 than the dominant Greek one, the sizable arrivals of the specific ethnic group might activate symbolic and cultural threat perceptions and therefore prompt opposing attitudes among the native population. It should be noted that recent studies show Greeks’ increased concerns about Islam and Muslims (Dixon et al., 2019; Lipka, 2018; Tent, 2017). Moreover, the recent sizable refugee influx partly coincides with a deteriorating economic environment due to the Greek recession, i.e. macro level conditions that according to realistic group conflict theory foster negative stances towards migrants (Kalogeraki, 2015). As Syrian refugees constitute an important segment of the recent refugee influx, I expect the specific ethnic group to attract unfavourable attitudes. Therefore, I hypothesise that opposition towards Syrian refugees is widespread in Greece (Hypothesis 1).

Attitudes towards migrants might range from strong opposition to strong support, i.e. including different levels of opposing and accepting attitudes (Abdel-Fattah, 2018). In the present study I expect that due to the perceived cultural and religious distinctiveness between Syria and Greece, individual determinants associated with social identity theory will be particularly important in shaping natives’ moderate acceptance and different levels of opposition towards Syrian refugees. However, strong opposition towards the specific ethnic group might be triggered by an amalgam of individual factors related with both realistic group conflict and social identity theoretical frameworks. Due to the recessionary conditions prevailing in the country a significant segment of the Greek population has suffered from record unemployment and poverty rates, therefore the massive refugee inflows might have triggered socioeconomic concerns motivating unfavourable stances. Drawing on the theoretical discussed arguments and the empirical evidence, the following hypotheses are examined:

Moreover, several studies have established links between specific demographic characteristics and opposition towards refugees. Recent meta-analytic reviews support that older age, being male and being resident in an urban setting are associated with unfavourable attitudes towards refugees (Anderson & Ferguson, 2018; Cowling et al., 2019). Therefore, I expect the specific demographic attributes to predict natives’ opposition towards Syrian refugees entering Greece (Hypothesis 4).

The chapter used a Greek dataset that derived from an online survey conducted during November and December 2016 within the context of the TransSOL project. Footnote 8 The Greek sample (n = 2061) was matched to national statistics with quotas for education, age, gender and region. Since I explored Greeks’ attitudes towards a specific ethnic group, i.e. Syrian refugees, the analysis excluded from the initial sample migrants. In the chapter migrants were operationalised as individuals whose parents and who themselves were born abroad (Dumont & Lemaître, 2005), therefore the number of observations used in the analysis was reduced from the initial sample size to n = 1975. In the sample 49.7% were men and 50.3% were women whereas the mean age was approximately 47 years old. Individuals with lower education (i.e. less than lower secondary education) accounted for 45.2% of the sample, whereas 35.7% and 19.1% had intermediate (i.e. upper secondary and post-secondary non-tertiary education) and higher education (i.e. university and above), respectively.

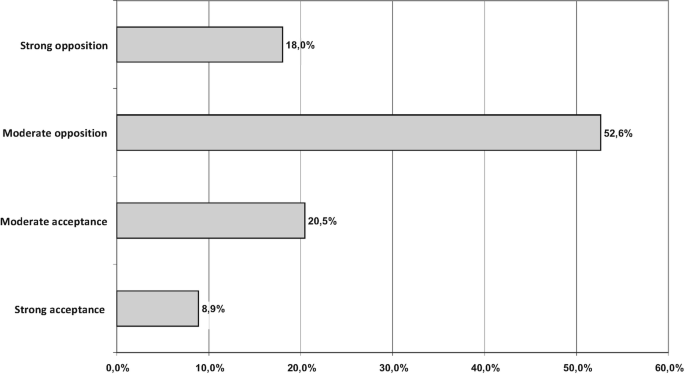

The survey included a question that asked respondents how they think Greece should handle refugees fleeing the war in Syria providing four responses: Greece a) should admit higher numbers than recently (labelled as ‘strong acceptance’ b) should keep the numbers coming here about the same (labelled as ‘moderate acceptance’), c) should admit lower numbers than recently (labelled as ‘moderate opposition’) and d) should not let anyone from this group come here at all (labelled as ‘strong opposition’). The question measured the level of acceptance/opposition towards Syrian refugees entering Greece.

Predictor variables involved a set of items capturing specific demographic characteristics and measurements of individual characteristics that in accordance to realistic group conflict and social identity theory are associated with attitudes towards migrants. With respect to the demographic characteristics, respondents’ gender, age, and area of living were included in the analysis. The latter was assessed with a recoded variable including individuals living in an urban area, a semi-urban area or a rural area.

Three indicators of socioeconomic status were used in the analysis to investigate the hypotheses associated with realistic group conflict theory including respondents’ educational attainment, income and occupational class. Educational attainment was measured with three responses including individuals with lower education (i.e. less than lower secondary education), intermediate (i.e. upper secondary and post-secondary non-tertiary education) and higher education (i.e. university and above). Income was measured with a question asking respondents on a ten-point scale for their household monthly net income after tax and compulsory deductions from all sources providing ten responses: a) less than 575€, b) 576€-775€, c) 776€-980€, d) 981€-1.190€, e) 1.191€-1.425€, f)1.426€-1.700€, f)1.701€-2.040€, g) 2.041€-2.500€, h) 2.501€-3.230€, i) 3.231€ or more. Respondents’ occupational class was assessed with a recoded variable including ‘low occupational class’ (such as skilled/semi-skilled or unskilled manual workers), ‘middle occupational class’ (such as clerical/sales or services/foreman or supervisor of other workers), ‘high occupational class’ (such as professional/managerial workers) and ‘other occupational class’ (such as farming, military workers).

The questionnaire included three questions related to social identity theory measuring on a five-point scale (‘Not at all attached,’ ‘Not very attached,’ ‘Neither,’ ‘Quite attached,’ ‘Very attached’) respondents’ level of attachment to different groups of people, including ‘people from your country of birth,’ ‘people with the same religion as you’ and ‘all people and the humanity.’ The recoded variables (‘Not attached,’ ‘Neither,’ ‘Attached’) assessed respondents’ level of identification with those born in their country and those of the same religion with them, as well as their level of identification with ‘all people and the humanity.’

The analysis involved descriptive and multinomial logistic regression analysis to explore Greeks’ attitudes towards Syrian refugees entering the country. The latter is used to predict the probability of category membership on the dependent variable measuring ‘moderate acceptance,’ ‘moderate opposition’ and ‘strong opposition’ compared to ‘strong acceptance’ of Syrian refugees based on the set of independent variables previously described. For the analysis data were weighted to match national population statistics in terms of gender, age and educational level.

Figure 5.1 shows that more than half of the Greek respondents (52.6%) expressed moderate opposition towards Syrian refugees and 18% adopted the most opposing attitude by supporting that Greece should not let any Syrian refugee entering the country. Approximately one out of five respondents (20.5%) showed moderate acceptance of Syrian refugees, whereas almost 9% strong acceptance of the specific ethnic group. The descriptive findings demonstrated that opposition attitudes towards Syrian refugees were prevalent among the Greek population.

Tables 5.1 and 5.2 present the descriptive analysis of respondents’ characteristics among groups reporting different attitudes towards Syrian refugees. As expected the most widespread response among respondents with different characteristics is reported for ‘moderate opposition’ (Table 5.1). Specifically, almost half of the male respondents (48.9%) and more than half of the female ones (56.4%) reported moderate opposition towards Syrian refugees entering Greece. Strong opposition towards Syrian refugees was higher among male respondents (22.4%) than female ones (13.5%). More men (10.5%) than women (7.2%) reported strong acceptance of the specific ethnic group entering the country, whereas the inverse findings were found for respondents reporting moderate acceptance. The vast majority of respondents living in rural areas (67.5%) reported moderate opposition towards Syrian refugees entering Greece whereas slightly more than half of individuals residing in urban and semi-urban areas reported similar stances. The highest prevalence of strong opposition towards the specific ethnic group (18.5%) as well as of strong acceptance (9.6%) was found for individuals living in urban areas compared to their counterparts in rural and semi-urban settings.

Table 5.1 Descriptive analysis of respondents’ age and income among groups reporting different attitudes towards Syrian refugees entering Greece

Table 5.2 Descriptive analysis of respondents’ age and income among groups reporting different attitudes towards Syrian refugees entering Greece

More than half of participants with different levels of educational attainment reported moderate opposition towards Syrian refugees, whereas the highest prevalence for the specific response was reported for respondents with higher educational attainment (58.4%). The highest prevalence of the most opposing stance towards Syrian refugees was found among individuals with lower educational attainment (25.3%), whereas strong acceptance of the specific ethnic group was higher among respondents with higher educational attainment (10.7%) than other educational background. With respect to respondents’ occupational class, more individuals belonging to the higher occupational class (57.4%) compared to respondents in other occupational classes reported moderate opposition towards Syrian refugees entering Greece. The highest prevalence of strong opposition was reported among individuals belonging to the ‘other’ occupational class (27.7%) whereas strong acceptance of Syrian refugees was higher among individuals of the lower occupational class (13.0%) than the other occupational classes (Table 5.1).

The analysis indicated that the most widespread response among respondents with different degrees of attachment to different groups of people, as indicators of social identity theory, was reported for the moderate opposition towards Syrian refugees. The highest prevalence of strong opposition was found among respondents that do not feel attached to ‘all people and the humanity’ (26.4%). Favourable attitudes towards Syrian refugees related to strong (16.3%) and moderate acceptance of the specific ethnic group (23.9%) were found among individuals that feel attached to ‘all people and the humanity.’

Moreover, the descriptive analysis showed that more than half of the Greeks who feel attached to the people born in their own country (55.5%) reported moderate opposition towards Syrian refugees. The highest prevalence of strong opposition towards the specific ethnic group was found for Greeks who do not feel attached to the people born in their own country (23.7%). Strong acceptance of the Syrian refugees was higher among individuals that do not feel attached (11.0%) or feel neither detached nor attached to the people born in their own country (11.6%). The prevalence of responses associated with strong (19.4%) and moderate opposition (60%) towards Syrian refugees entering Greece was higher among individuals attached to the people of their own religion. The prevalence of responses related with strong acceptance of the specific ethnic group was higher among Greeks who do not feel attached to the people of their own religion (13.5%) (Table 5.1).

Table 5.2 shows that the mean age of respondents reporting strong opposition towards Syrian refugees was higher (M = 49.09, SD = 14.39) than those with less opposing stances. The lowest mean age was reported for individuals reporting moderate acceptance of the specific ethnic group (M = 45.30, SD = 15.51). The most opposing attitude towards Syrian refugees was found among respondents with the lowest mean income (M = 3.30, SD = 2.28) whereas individuals reporting moderate acceptance of the specific ethnic group have the highest mean income (M = 4.27, SD = 2.40).

Table 5.3 presents the multinomial logistic regression analysis for the variables predicting membership in the groups of ‘moderate acceptance,’ ‘moderate opposition’ and ‘strong opposition’ towards Syrian refugees compared to the ‘strong acceptance’ group (reference group). Respondents’ gender, occupational class and level of attachment to ‘all people and the humanity’ were significant predictors in differentiating the ‘moderate acceptance’ group from the reference group. Specifically, male respondents were less likely to be in the group of respondents showing moderate acceptance towards Syrian refugees rather than the group fully accepting them. Furthermore, respondents of middle occupational class as well as those reporting that they are not attached or feel neither detached nor attached to ‘all people and the humanity’ were more likely to express moderate acceptance towards Syrian refugees compared to the reference group.

Table 5.3 Multinomial logistic regression analysis for the variables predicting membership in groups of ‘Moderate acceptance,’ ‘Moderate opposition’ and ‘Strong opposition’ compared to ‘Strong acceptance’ of Syrian refugees entering Greece (n = 1698)

In the comparison of survey respondents with moderate opposition towards Syrian refugees to those that fully accepting them, all the indicators related with social identity theory as well as respondents’ gender and area of living were significant predictors. Specifically, male respondents and those residing either in urban or rural areas were less likely to be in the group of respondents showing moderate opposition rather than the group fully accepting Syrian refugees. Moreover, respondents reporting lack of attachment or feeling neither detached nor attached to ‘all people and the humanity’ were significantly more likely to express moderate opposition. Furthermore, attachment to the people from respondents’ country of birth and from the same religion predicted membership in the group of moderate opposition rather than the group of respondents fully accepting Syrian refugees (Table 5.3).

All variables under study, except from the attachment to people from respondents’ country of birth, became significant predictors in differentiating the respondents who strongly oppose Syrian refugees from those who fully accept them. Specifically, older individuals were more likely to strongly oppose Syrian refugees rather than to strongly accept them. High earners, male respondents as well as respondents living in urban or semi-urban areas were less likely to strongly oppose Syrian refugees compared to the reference group. Indicators of socioeconomic status, such as the lower educational attainment, the lower occupational class and the ‘other’ occupational class predicted membership in the group of ‘strong opposition.’ Additionally, lack of attachment to ‘all people and the humanity’ but strong attachment to the people of the same religion predicted membership in the group of ‘strong opposition’ rather than the reference group. It should be noted that the Odds Ratios (ORs) of the specific indicators were increased, indicating that these attributes related to social identity theory were particularly important in differentiating strong opposition towards Syrian refugees rather than fully accepting them.

In 2016, the closure of the Balkan route and the EU-Turkey Statement led to the decline of refugee inflow; however, a high number of refugees were left stranded in Greece waiting for relocation or for getting integrated into the country (European Commission, 2017). The present chapter inspired by the realistic group conflict and social identity theoretical frameworks (Blalock, 1967; Blumer, 1958; Bobo, 1999; Sherif & Sherif, 1979; Tajfel, 1981, 1982) examined specific determinants forming Greeks’ attitudes towards Syrian refugees during the recent ‘refugee crisis,’ which as discussed earlier, in the present chapter it refers to the perspectives of the host countries and the challenges they face due to the large groups of refugees entering their borders. The findings provide some preliminary evidence that the ‘refugee crisis,’ i.e. the sizable refugee influx in Greece as well as the recessionary conditions prevailing in the country might have triggered socioeconomic concerns and symbolic threats (Kalogeraki, 2015; Lahav, 2004; Semyonov et al., 2008; Sides & Citrin, 2007; Chap. 6 in Fokas et al., this volume). Such threats, in line with the hypotheses, have activated extensive opposition towards Syrian refugees (including both moderate and strong opposition) as approximately seven out of ten Greek respondents reported such a negative stance. Similar anti-refugee sentiments have been also reported in the city of Athens receiving large numbers of refugees and asylum seekers from the Aegean islands (Chap. 14 in Stratigaki, this volume). For instance, local citizens reacted negatively for the access of refugee children to specific schools, for renting out apartments to host refugees and in some cases locals expressed their discomfort when meeting Syrian women wearing their headscarves.

Due to the cultural and religious distinctiveness between Syria and Greece, natives’ concerns about refugees’ potential impact on the Greek customs and traditions may have played a decisive role in triggering widespread opposition (Adida et al., 2019; Bansak et al., 2016; Ivarsflaten, 2005). Accordingly, several studies have shown that host populations prefer migrants from originating countries whose cultures are perceived as similar to their own (Dustmann & Preston, 2007; Hainmueller & Hangartner, 2013). Moreover, research suggests that host populations prefer migrants whose faith and traditions match the host countries’ dominant religion (Adida et al., 2019; Laitin et al., 2016). For instance, Bansak et al. (2016) argue that in traditionally Christian societies, religious concerns are crucial in shaping unfavourable attitudes towards Muslim asylum seekers.

In accordance with the aforementioned arguments, specific factors related to cultural or identity concerns as developed in social identity theory (Davidov et al., 2008; Sides & Citrin, 2007; Sniderman et al., 2004; Tajfel, 1981, 1982) were particularly important in understanding Greeks’ different levels of opposition towards Syrian refugees. The analysis demonstrated that individuals who strongly identified with people born in Greece and with those of their own religion, as well as individuals feeling detached from all other people and from the humanity were more likely to oppose Syrian refugees entering the country. Although strong attachment to people born in Greece became a non-significant predictor for individuals strongly opposing the specific ethnic group, the increase in ORs in the rest social identity indicators indicated the decisive role of the specific determinants in shaping extreme opposition towards Syrian refugees.

As many Syrian refugees are Arabs and Muslims, they are likely to activate symbolic threats escalating concerns on the potential incompatibility of refugees’ value and belief system with the dominant culture and with Greek Orthodoxy as the dominant religion in the country. Despite the visibility of Islam in the Greek public sphere Footnote 9 and the gradual transformation from a relatively culturally and ethnically homogenous society into a more diverse one (Cavounidis, 2013) hosting a significant number of Muslim migrants (Sakellariou, 2017), the native population seems to be reluctant in accommodating the cultural, ethnic and religious diversity of Muslims (Lipka, 2018; Tent, 2017). For instance, Dixon et al. (2019) found that the majority of the Greek population expressed increased anxiety about the potential incompatibility of the Greek culture and the Islam religion. Nevertheless, similar anxieties about Islam and Muslim migrants’ cultural incompatibility with the western customs and way of life are widespread among most European populations (Wike et al., 2016) indicating that such perceptions might negatively affect attitudes towards migrants of the specific cultural and religious background.

The hypothesis on specific demographic characteristics was confirmed only with regard to age: older natives strongly opposed Syrian refugees entering the country. However, contrary to our expectations, men and individuals residing in urban areas were less likely to express such negative stances. As women have been particularly affected during the recent economic downturn (Anastasiou et al., 2015), it is likely that their socioeconomic concerns are more strongly heightened than those of men, and consequently that their opposition towards Syrian refugees is higher. Moreover, as migrants usually reside in urban areas, natives have more opportunities for intergroup contacts and interactions, which usually ameliorate negative attitudes towards migrants (Escandell & Ceobanu, 2009). In agreement with our expectations, extreme opposition towards Syrian refugees is not only shaped by individual factors related to social identity theory, but also to realistic group conflict theory. The analysis indicated that individuals of lower socioeconomic status, i.e. of lower income, educational attainment and occupational class, were more likely to strongly oppose Syrian refugees rather than fully accept them. The recent recession has intensified socioeconomic perceived threats among natives of lower socioeconomic status (Kalogeraki, 2015) who are likely to compete for similar positions with Syrian refugees in the labour market. Providing empirical support to realistic group conflict theory, concerns over scarce economic resources might have activated extreme opposition towards the specific ethnic group among natives in the lower positions of the social ladder. The aforementioned findings underscore that the profile of the native population strongly opposing the specific ethnic group includes an amalgamation of individual attributes related with both cultural as well as socioeconomic determinants.

Both cross-sectional (e.g. Dixon et al., 2019) and cross-national studies (e.g. Wike et al., 2016) underscore the relatively high prevalence of unfavourable attitudes towards refugees among the Greek population. Nevertheless, such empirical evidence lacks a thorough investigation of the main determinants shaping such negative stances specifically towards Syrian refugees, who constitute an important segment of the refugee population in Greece. The chapter sheds some empirical light on key individual level factors that trigger anti-refugee sentiments/attitudes towards Syrian refugees; therefore, it empirically enriches a relatively under-researched issue for the Greek case. At the theoretical level the chapter contributes to migrant related research on the significance of realistic group conflict and social identity theories to examine key factors shaping natives’ attitudes towards migrants.

To mitigate the anti-refugee sentiments/attitudes, policy initiatives need to be designed (see e.g. Chap. 13 in Tramountanis, this volume) that aim at curtailing the main sources of negative stances. These interventions may involve cultural diversity programmes targeting the promotion of intercultural dialogue which may counter Greeks’ socio-economic and mostly cultural concerns about the potential impacts of Syrian refugees on the country.

It should be noted that even though Syrian refugees continue, even nowadays, to be an important segment of the refugee population in Greece, recent data demonstrate that top refugee nationalities also include Afghans (UNHCR, 2020). Due to the lack of questions on attitudes towards refugees of different ethnic backgrounds in the questionnaire, the present chapter is limited specifically to Syrian refugees. Studies investigating natives’ attitudes towards different ethnic groups and types of migrants are exceptionally scarce (Hellwig & Sinno, 2017). However, migrants of different ethnic origins might trigger different concerns and consequently attract different attitudes among host populations (Ford, 2011). Future studies may examine whether refugees of different ethnic backgrounds and qualities activate different types of socioeconomic and cultural threat perceptions, as well as explore the mechanisms that each of these threats, activate negative stances.

Under international law, the term ‘refugees’ refers to individuals who have been forced to flee their home country due to conflicts, persecution and man-made or natural disasters. The term ‘asylum seekers’ refers to individuals seeking protection in the country they are in, but their application for refugee status is still being processed. Since some rejected asylum seekers may be refugees, the term ‘refugees’ is used in the chapter to refer to both to asylum seekers and refugees.

Also referred to as ‘migrant crisis.’ The highest prevalence is reported for Hungary.More information for the project ‘European Paths to Transnational Solidarity at Times of Crisis: Conditions, Forms, Role Models and Policy Responses’ (TransSOL) can be found at: http://transsol.eu/

In the chapter the term ‘migrant’ is used as an umbrella term to refer to any person who moves away from his or her place of usual residence, whether within a country or across an international border, and regardless of whether the movement is ‘forced’ or voluntary.

It should be noted that although Syria has no official religion, approximately 85% of the population is Muslim, and of these, 85% are Sunni Muslims (Kurian, 1987).

The survey data used in the chapter derived from Work Package 3 (‘Online Survey: Individual forms of solidarity’) of the project. More information for the specific Work Package and the methods applied see the Integrated Report (TransSOL, 2017).

10It should be noted that in Greece, there is an indigenous Muslim minority located in Western Thrace, including 110,000–120,000 Muslims of Greek citizenship that enjoy a number of minority rights.

Data presented in this chapter have been collected as part of the project ‘European paths to transnational solidarity at times of crisis: Conditions, forms, role models and policy responses’ (TransSOL). The project received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 programme under grant agreement No 649435. The TransSOL consortium is coordinated by the University of Siegen (Christian Lahusen), and is formed, additionally, by Glasgow Caledonian University (Simone Baglioni), European Alternatives e.V. Berlin (Daphne Büllesbach), Sciences Po Paris (Manlio Cinalli), University of Florence (Carlo Fusaro), University of Geneva (Marco Giugni), University of Sheffield (Maria Grasso), University of Crete (Maria Kousis), University of Siegen (Christian Lahusen), European Alternatives Ltd. LBG UK (Lorenzo Marsili), University of Warsaw (Maria Theiss), and the University of Copenhagen (Hans-Jörg Trenz).